You can’t memo or force your way to AI adoption. I’ve written before (Strategy Isn’t Strategy Unless Repeated) about why communication alone doesn’t change behavior. Adoption is a behavior change problem. You need mechanisms of change, not just announcements.

Two that have worked well for me for AI adoption specifically are: hackathons and local champions. Hackathons (Using Hackathons to Drive Real AI Adoption) are the spark because they create permission, surface potential, and, through their peers and colleagues, show people what’s possible. But they’re events. The energy from them fades quickly. The question is what keeps adoption moving between the events. That’s where your local champions come in.

What Happens When You Do Nothing

When you let AI adoption happen organically, what you actually get is a widening gap. A few people figure it out on their own because they’re already curious and already experimenting. Most don’t. They’re busy and already have their workflows. The tools feel like one more thing on the pile.

Training doesn’t solve this either. At least not the way most companies do it. Standalone training is a checkbox. People complete the modules, do their “Hello World”, and go back to their real work. There’s no destination to build their excitement. No connection to a problem they actually have. It’s education without motivation, and motivation is the hard part.

The gap compounds. The early adopters get faster, produce better work, and start pulling away from the rest of the team. Two months later (AI moves quickly), you have a bifurcation within the team: there is a handful of people who can’t imagine working without AI and a group who’ve barely touched it. The absence of an adoption strategy is itself a decision. It tells your org that you’re fine with the split.

There’s a second cost that’s easier to miss. Your best people, the ones leaning in, are watching whether the organization is keeping up with them. Top talent wants to work at places that match their vibe and their pace. If you make them use new tools under old constraints, or treat adoption as optional, they’ll eventually find somewhere that doesn’t. It’s the same logic as the old training question: “What if we invest in people and they leave? What if we don’t and they stay?” With AI adoption, there’s a third option that’s worse than both: you don’t invest, and they leave.

Find Your Champion

If you’ve been around enterprise sales, you’ve probably seen MEDDPICC (Metrics, Economic Buyer, Decision Criteria, Decision Process, Paper Process, Identify Pain, Champion, and Competition). We’re selling a new way of working into our organizations and we need to find our Champion. In the framework, a champion is someone with credibility and influence inside the buying org who actively sells on your behalf. Not because you asked nicely, but because they believe in the outcome. You don’t sell to the whole buying committee. You find your champion, arm them, and let them do what you can’t: influence from the inside.

AI adoption works the same way. In every department, there’s someone who’s already leaning in — or could be with a little investment. Your job as a leader isn’t to convince the whole team. It’s to find that person and make them wildly successful. Their results do the convincing for you.

Don’t forget that your org chart doesn’t dictate your influence map. The champion is often not the team lead or the department head. It’s whoever has the right combination of curiosity, credibility with their peers, charisma, enthusiasm, and willingness to show their work publicly. Sometimes it’s the most junior person on the team. Sometimes it’s someone in a completely different department.

That last point becomes more important the higher up you are in the org chart. If you’re a CTO or a senior executive, your champions aren’t limited to your own org. You can spot these people in different departments across the company and support them from the outside. Give them air cover. Connect them with your technical team to accelerate their capabilities. Help them go further than they could go alone. You don’t need to own the department to enable the person.

Influence and charisma beat authority in behavior change. Once you’ve found your champion, back them. Don’t use them as a mouthpiece for leadership, but focus on them as an organizer. Have the champion pull together the people around them. Here, it’s more about small groups, local to their team, who are working through similar problems. This works because the champion is a peer, not a manager. When your team lead says “you should try using AI for this,” it’s a directive. When the person next to you, doing the same job, dealing with the same frustrations, shows you how they solved something in twenty minutes that used to take a day, that’s leading through influence. It’s like the gym: you don’t get energy and then go. You go, and the energy comes. The champion’s early success creates the momentum for the people around them to start. Peer-driven change doesn’t trigger the same resistance as top-down mandates. It doesn’t feel like a corporate initiative. It feels like colleagues sharing something useful.

The leader’s role here isn’t to run the group or set the agenda. It’s to recognize the champion, give them the space, and make sure they know they have support. The organizing energy comes from the champion. The air cover comes from you. Once people are convinced, you can swoop in with the training and enablement.

Shifting the Internal Baseline

One person on our strategy team started building pre-sales tooling with AI. Specifically, they built an onboarding tool that mirrors our existing sales and onboarding workflows. This helped the sales reps get up to speed faster on a new offering and demo more effectively without waiting for someone to walk them through every detail one at a time.

The tool wasn’t “engineering spec” perfect. But it didn’t need to be. It did the job better and faster. It’s hard to argue with a working demo. When the rest of the strategy, pre-sales, and sales teams saw what was possible — the speed, the quality, and the fact that one person built it — the baseline shifted.

Now the rest of the team is adapting. Not because someone set a mandate. Not because there was a training module. But because someone on their team demonstrated a new standard, and the gap between “how we’ve been doing it” and “how it could be done” became visible and undeniable. The champion didn’t need a title or a directive, they needed room to run. And they needed to know that this kind of initiative is what the org actually wants, not just tolerates.

Make the Work Visible

Give champions room to run and they’ll create proof points. But a proof point only works if people see it. If the strategy team’s onboarding tool lives in one person’s demo and one team’s Slack channel, the effect stays local. You need mechanisms that make the work repeatedly visible across the org.

We run a weekly show-and-tell where anyone can present what they’ve built. It doesn’t have to be finished or polished. The point is exposure to ideas: people seeing what’s being built, how fast it can be built and iterated on, and what problems are being solved.

We also run a #topic-inspirations channel in Slack where people share tools, prototypes, and vibe-coded projects built outside the company, and explain why they’re interesting. This expands the frame of reference. It’s not just “AI is coming.” It’s “look what people are already building, right now, everywhere.” It sets the context for what’s possible.

Then there’s #topic-prototypes, where people share what they’ve built internally. This is the lower-barrier version of the show-and-tell. It’s available all the time and for people who’d rather share asynchronously or aren’t ready to present live. Plus there is immediate discussion that you don’t get during presentations. But it’s also where the external inspiration becomes personal. The inspirations channel shows you what the world is doing. The prototypes channel shows you what your peers are doing. That’s the one that usually hits home.

This creates a specific kind of productive peer pressure. When you see someone from a completely different team demo a tool they built in an afternoon that solves a problem you’ve been dealing with for months, it recalibrates your sense of what’s possible. And when it happens with regularity, it becomes hard to sit on the sideline. These channels are also where your champions, the most vocal and enthusiastic people, gravitate to the same conversations.

But inspiration without enablement creates frustration and potentially resentment. It’s easy for someone to watch a show-and-tell, get excited, open a tool, and immediately feel lost. That’s where targeted training closes the gap. Not training as a standalone program either. It needs to be training that gives people just enough to mimic what they saw. The champion built an onboarding tool? Show people how to prompt effectively for that kind of output. Someone demoed a workflow automation? Walk through the first three steps. The goal isn’t mastery, it’s a first successful attempt. It’s making the mountain of learning feel like a molehill.

There’s a third channel that serves a different purpose: #topic-ai-support, where anyone can ask questions. This is including questions that they may feel are stupid. How do I get Claude to stop hallucinating this API end point? Why isn’t my prompt doing what I want it to? Can someone explain what a repo is? How do I even start? This channel has to be actively protected. The moment someone gets a dismissive response or feels judged for not knowing something, the tone changes and the channel goes silent. And with it goes the fastest path for people who are willing to try, but aren’t yet confident. Visibility and pressure only work if there’s a safe space to be a beginner. Without it, the people in the middle of the adoption curve, the ones who are curious but uncertain, will continue to just watch from the sidelines instead of jumping in. The show-and-tell creates aspiration. The training creates a bridge. The support channel creates permission.

None of this is accidental culture. The weekly cadence, the Slack channels, the low barrier to sharing — it’s all designed to keep adoption visible and normal. The more people see their peers building, the more building feels like the default rather than the exception. When you’re asking everyone to move faster through the adoption curve, you have to make it accessible.

Let the Process Catch Up

As adoption picks up, some of your existing processes will start to feel out of place. That’s probably because they are. AI changes the cost and speed of certain kinds of work, and that means the sequence you’ve always followed may no longer make sense.

Here’s a simple example: we used to write a PRD, get alignment, and then build. That’s a reasonable workflow when building is expensive or time consuming. But when someone can prototype a working version in an afternoon, the smarter move is often to build first and write the PRD once you’ve validated the idea. The PRD becomes a document that captures what you learned, not a speculative document that guesses at what you’ll build.

This isn’t about abandoning rigor. It’s about being honest that AI changes the economics of certain steps. Refusing to adjust your process is its own kind of rigidity. Some processes will shrink. Some will move. Some will disappear entirely. If you’re serious about adoption, you have to be willing to let the workflow evolve alongside the tools. Otherwise you’re asking people to use new tools inside old constraints, and they’ll feel the friction of that choice every day.

Your local champions will surface these friction points before anyone else. They’re the ones hitting process walls first because they’re moving fastest or just operating differently. Pay attention to where they’re getting stuck or slowed down. When a champion tells you the approval workflow doesn’t make sense anymore, or that a review step is now the bottleneck instead of the build, that’s not a complaint. That’s a signal about which processes require review.

Why Pushing Is the Kind Thing to Do

Left alone, most people will stay where they’re comfortable. That’s human nature, not a character flaw. We all default to the familiar until something forces us out of our comfort zone and into change.

But the world is changing whether your team opts in or not. The tools are getting better every month. The expectations are shifting and the goalposts are moving. The people who aren’t building these skills now will be materially behind in just a few months.

This is where I think a lot of leaders get it wrong. They frame adoption as optional, “here are the tools, use them if you want.” It feels respectful because they don’t want to be heavy-handed. But that’s actually the less kind option. You’re letting people fall behind because pushing feels uncomfortable for you.

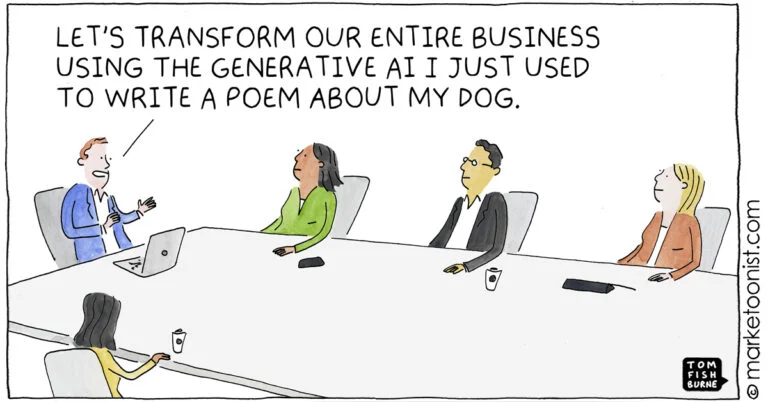

The other version of this mistake is making adoption mandatory but skipping the infrastructure: no champions, no visibility, no training with a destination, no safe place to ask questions. Just a mandate and a deadline. That gets the direction right but with none of the mechanics. People comply without adopting and you end up with checkbox completion, not behavior change.

The kind version is the harder one: push and invest. Nudge people along the adoption curve while giving them every reason and resource to move. You are not dragging people because you’re impatient with their pace. You are pushing because you can see where things are going and you’d rather they be ready than surprised.

That’s what it means to actually care about your people’s growth, not just their comfort. Sometimes caring about someone means making them uncomfortable now so they’re not in crisis later.

This Is All Culture

Every decision you make, and every decision you don’t make, defines your culture. Running a hackathon is a culture statement. Investing in your champions is a culture statement. Building visible channels, targeted training, and a safe place to ask beginner questions; these are all culture statements. Letting the gap widen because you don’t want to force change on people; that’s a culture statement too.

Culture isn’t what you put on a slide. It’s what you do repeatedly when it’s inconvenient. Culture is how people behave when no one is telling them how to operate. If your culture is about making people better, genuinely better, then building these mechanisms is what that looks like in practice.

Hackathons to create the spark. Champions to sustain it. Visibility to create momentum. Training to close the gap. Support to make it safe. And a willingness to keep pushing even when people would rather stay where they are.

Adoption strategy is culture strategy, whether you frame it that way or not.