Building software is easier than ever. The AI tools work well enough. The low-code/no-code platforms work well enough. The vibe coding works well enough. That marketing director who shipped an internal tool over the weekend? They’re not wrong to feel empowered. They actually built something, it actually runs, and it solves the problem that they set out to solve. But there’s a dangerous conclusion spreading through organizations right now: if building is easy, what do we need all these developers for?

Like many other tech leaders, I’ve been watching this play out in real-time. A non-technical executive recently vented to me about dismissing the engineering team’s concerns on speed, while simultaneously bragging about what his team “can do” with AI tools. The executive isn’t entirely wrong. Their team can build things now. But they don’t know what they don’t know.

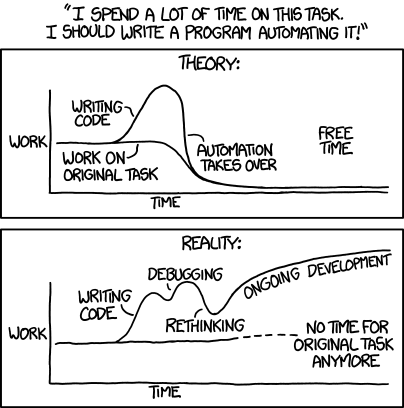

Building software was never the hard part. It was just hard enough that we never had to fully explain what comes after.

What Building Used to Teach

For decades, the difficulty of getting something working acted as a natural filter. If you could build it, you knew “done” was actually the starting line, not the finish line. Now that particular barrier has collapsed. And everyone’s going to learn what “operating a thing” actually means.

I’ve watched people outside traditional engineering roles — solutions architects, operations leads, product managers, executives — build some genuinely impressive prototypes recently. A CEO I know vibecoded a complete data processing system and is already in full-on sales mode with it. These solve real problems and the people who built them should feel good about that. But scaling software is a discipline unto itself, learned through production incidents, late-night debugging sessions, and years of watching others make mistakes while trying to avoid their own. Nothing in the building process teaches you that, and nothing in AI tooling surfaces it. Why would it? You asked for working software, and that’s what you got. The tools delivered exactly what was requested. The gap is in what the builders don’t yet have the experience to request.

It’s easy for everyone right now because few have hit the hard part yet. I’ll be the first to admit: AI dev tooling has had an outsized impact on my own work. As a tech executive, I still understand the patterns. I know what to check for, what questions to ask, and what good architecture looks like. But my actual hands-on development velocity? That’s rusted over after years of leading teams rather than writing production code. AI tools work around that rust beautifully. I can move faster and explore more ideas than I could five years ago.

But here’s what that experience has also reinforced: I’m building prototypes and proofs of concept. I’m exploring ideas and validating approaches. I’m not shipping production systems that need to run reliably at scale, handle edge cases gracefully, or stay maintainable when I’m not the one maintaining them. The tools help me build. They don’t help me operate. And I know enough to know the difference.

The executives dismissing engineering teams often don’t.

I’m not naive enough to think my prototypes will stay prototypes. Some will become production systems whether anyone likes it or not. Not by design, but because they work well enough that nobody wants to rebuild them properly, they’ve already been sold to customers, or they’re being used in a beta state that quietly becomes production-critical to internal or customer workflows. That’s how it always happens.

The difference here isn’t intelligence or even technical skill, it’s (often hard-earned) experience. It’s knowing what productionization actually requires. This is the gap between “it works” and “it works reliably at standard usage patterns with real users and real consequences.” That knowledge comes from years of doing it wrong, then doing it right, then watching others make the same mistakes. It doesn’t come from the building process itself, no matter how good the tools are.

For most of the organization, these concerns were always the “tech org’s problem.” These were things that just happened somewhere else. Now that building looks easy, they’re being asked questions they never wanted to know the answers to.

The Great Filter

The Fermi Paradox (one of my favorite explanations OR wikipedia) asks a simple question: if the universe is so vast and so old, where is everyone? Statistically, we should see evidence of other civilizations. We don’t. One proposed answer is the Great Filter, that there is some barrier so difficult to pass that most civilizations never make it through. The debate is whether that filter is behind us (we already passed it) or ahead of us (we’re doomed like everyone else).

Software companies have their own version of this. Tens of thousands of startups launch every year. A tiny fraction survive to meaningful scale. For decades, we assumed the filter was building something people wanted, the product-market fit problem. If you get past that, you’ve figured out the hard part. But there’s always been a second filter: operations. This includes things like simply operating what you built, keeping it running, scaling it, monitoring it, securing it, making it compliant, and maintaining it as the world changes around it. This filter was less discussed because the first filter, just building the thing, was selective enough to correlate with operational capability. If you could build it, you probably understood enough to run it.

That first filter just got a lot easier to pass. Which means more people, and more organizations, are going to hit the second one without the preparation that the building difficulty used to provide. There’s no universal timeline for this. Organizations with aggressive AI adopters pushing tools into production will hit the filter first. More conservative shops will hit it later. But the variable is adoption speed, not whether it happens. The Great Filter for software didn’t disappear. It moved downstream, and a lot of organizations are about to discover it’s still there.

The Iceberg They Can’t See

When a team builds software, multiple people look at it. Product management, design, engineering, devops all weigh in at some point in the cycle. Each brings different questions and perspectives. Will this scale? What happens when users do something unexpected? How do we know if it’s working? AI-assisted solo development removes that friction, even though friction was doing real (and important) work. You end up with one person and a model optimizing for “does it run?” Nobody’s asking the uncomfortable questions because there’s nobody else in the room.

Many of the processes that feel slow or unnecessary in mature engineering organizations aren’t bureaucracy for its own sake. They exist because something broke badly enough that the organization decided it should never happen that way again. Over time, the original failure fades from memory, but the process remains. When new tools make it possible to bypass that process entirely, it’s easy to have organizational amnesia and conclude that the process or checklist may not have been necessary in the first place. Sometimes that’s even true. Processes can outlive their relevance when the underlying conditions change. But there’s a difference between an experienced technical leader, product manager, or engineer rethinking a process because they understand why it existed in the first place, and a new builder skipping it because they never knew it was there. You need to know the rules to break them effectively. The new builders haven’t had to learn these lessons yet. They skip the processes they don’t know exist and dismiss the ones they do without understanding why they were there in the first place.

This matters because operational concerns are invisible until they’re not. Monitoring, alerting, security, compliance, incident response, dependency management are all incredibly important topics. Experienced engineers build these in because they’ve been burned by their absence. But nothing in the building process actually surfaces them. The AI doesn’t ask “how will you know when this breaks?” because you didn’t ask it to. The result is software that works until it doesn’t; often with no instrumentation to tell you why.

Anyone who’s operated software at scale knows these concerns exist. The less experienced people building AI-generated tools to solve their immediate problems often don’t, and likely won’t, until the first production incident with a system nobody fully understands.

Yes, AI will get better at operations too. It will plug into monitoring tools, flag anomalies, maybe even suggest fixes. But someone still has to decide which fix is appropriate, what the second-order consequences are, and whether the suggested solution creates new problems. That judgment comes from experience, and experience comes from doing the work. If AI handles the building, fewer people get the reps that develop operational intuition in the first place.

Shadow IT Becomes Shadow Liability

This is where Shadow IT becomes useful rather than just a compliance headache. I’ve written before in, Shadow IT isn’t a Threat, It’s a Signal, about how it reveals the people closest to customer problems routing around bottlenecks to find solutions. That perspective hasn’t changed, but the risk profile has. We’ve moved from unsanctioned spreadsheets to unsanctioned AI-generated applications handling live customer data.

The response isn’t to crack down harder. That just drives the activity underground and loses the signal entirely. The response is to use Shadow IT as a way to identify who’s building, what they’re trying to solve, and where they need support. These are often your most motivated problem-solvers. They just don’t know what they don’t know yet.

Create legitimate paths for this energy: contained environments where experimentation can happen without putting the organization at risk. Make it easier to do the right thing than the risky thing. Guide and support rather than gatekeep and block. Because the alternative is discovering these shadow tools only when they fail—and having no one who understands them well enough to fix them.

What AI Actually Produces

AI builds exactly what you tell it to build. This sounds obvious, but the implication is easy to miss: the tools are training builders to be specific about what they want. That’s a useful skill. The problem is that specificity about the wrong things produces precisely-built software that’s missing everything someone didn’t know to ask for.

You get documentation that describes what the code does without explaining why it exists. Tests that achieve coverage metrics without hitting all the meaningful things required to be tested. Features that work exactly as specified but become obstacles when your understanding of the product evolves. You didn’t ask for extensibility, and even if you had, you didn’t yet know what kind you’d need.

Experienced engineers know what to ask for because they’ve built systems that failed in specific ways. They ask about monitoring, logging, and stats for introspection because they’ve debugged outages with no visibility. They ask about edge cases because they’ve watched “impossible” inputs take down production. They also know where systems typically need flexibility later and build in those accommodations early, not because anyone asked, but as a safety net against requirements that haven’t been written yet. The tools can’t teach you what questions to ask. They can only answer the questions you already know to raise.

What This Means for Technical Leaders

This isn’t about defending developer jobs. Developers who only knew how to build were always going to have a hard time as building got commoditized. This is about helping organizations understand where actual risk lives now. The value of experienced engineers was never primarily in typing code faster. It’s in knowing what breaks, when it breaks, and how to design systems that fail gracefully instead of catastrophically. It’s in having seen enough go wrong to build things that anticipate going wrong.

Your job as a technical leader now includes translating this reality before your organization learns it the hard way. That means being concrete about what “production-ready” actually requires. It means making the invisible work visible without being defensive about it. It means helping non-technical colleagues understand that their skepticism about engineering complexity is sometimes warranted, and that their confidence about what’s easy is sometimes dangerously misplaced.

Concretely, before the first AI-built tool becomes production-critical, establish what “production-ready” actually means in your organization. Not as a gate designed to slow things down, but as a short conversation between the builder and someone who’s operated software at scale. What happens when this breaks? How will you know? Who gets paged? Where does customer data live? Make the checklist explicit so the gap becomes visible before it becomes a crisis.

The filter didn’t disappear — it moved. And unlike product-market fit, there is no pivot that gets you around operational failure.