Growing engineering organizations face a communication problem that more meetings won’t solve.

When you’re small, decisions happen naturally. Everyone knows what everyone else is working on. You can sit around a table and discuss problems and solutions. But as you add engineers and teams, that breaks down. You start seeing the symptoms: conflicting architectural decisions made in isolation, the same debates happening repeatedly, knowledge trapped in whoever happened to be in the room.

The instinct is to add synchronization. More standups. More cross-team syncs. More Slack channels. That usually makes things worse. It creates a meeting culture, where decisions require getting everyone in a room, and nothing moves until calendars align.

What actually works is formalizing how decisions get made and documented. RFCs, Requests for Comments, sound bureaucratic. But done right, they’re actually the opposite. They reduce the need for meetings by creating a shared artifact that travels without the creator. Engineers can review asynchronously. Decisions become discoverable. Context gets distributed without requiring everyone’s simultaneous attention.

What’s an RFC?

RFC stands for Request for Comments. The format originated in 1969 with the development of ARPANET—Steve Crocker started writing them as a way to document early internet protocols without claiming to have all the answers. The name is intentional: it signals that the document is open for feedback, not a decree from on high. In practice, this is the cultural lever that makes the process work; it invites collaboration rather than defensive posturing.

Modern engineering organizations have adopted the format for internal decision-making akin to a Product spec from Product Management. An RFC is a written proposal for a significant technical change. It typically describes the problem, the proposed solution, alternatives considered, tradeoffs, and some additional useful metadata.

Why Formalization Matters as You Scale

Somewhere around 20-25 engineers or 3-4 Engineering teams, communication overhead starts to outpace your ability to manage it informally. Context stops traveling naturally. You can no longer assume that the right people heard about a decision, understood the reasoning, or know where to find it later.

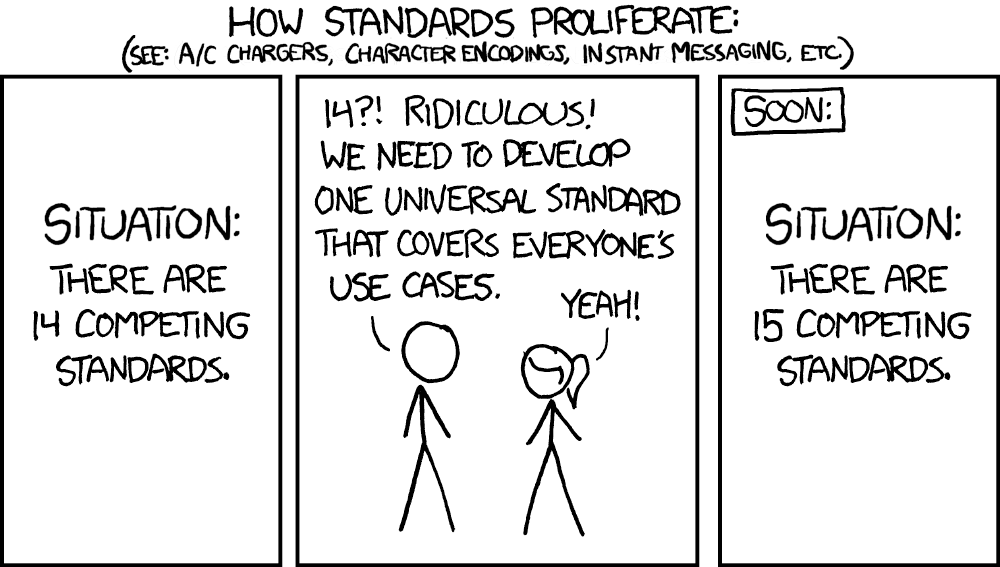

Without some formalization, you get one of two failure modes. Chaos: every team does their own thing, and you discover incompatible decisions later when systems need to integrate. Or bottlenecks: everything flows through a handful of senior people who become the organizational constraint.

RFCs solve this by making decisions visible, reviewable, and discoverable without requiring a meeting for every decision. They create shared context that scales with headcount instead of against it. Code tells you what’s happening, the RFC tells you why it wasn’t done another way. It turns tribal knowledge into archeological records.

What RFCs Actually Accomplish

When you require engineers to write an RFC before implementing a significant change, several things happen.

- They have to think it through. The act of writing forces clarity—vague ideas become concrete when you have to put them into words. But the RFC template forces something more: systematic thinking. Sections like “alternatives considered” and “tradeoffs” make engineers address questions they might otherwise skip. This happens before code gets written, when changing direction is cheap.

- You create institutional memory. Documentation becomes communication—decisions, as well as objections, are discoverable months or years later. When someone asks “why did we build it this way?” the answer exists. When a new engineer joins, they can read the RFC and understand not just what was decided, but why and what else was tried.

- You surface cross-team conflicts early. An RFC that affects the API contract gets reviewed by the teams that consume that API. Dependencies become visible before they become surprises. It also ingrains larger scope thinking earlier in the process and builds the muscle of being a good citizen within an organization by regularly considering others.

- You empower decision-making without meeting overload. An engineer can write an RFC, circulate it for async review, incorporate feedback, and move forward—all without blocking on calendar availability. The decision-making process becomes documentation-driven rather than meeting-driven.

- You tap into experience you didn’t know existed. When you’re adding a new technology or implementing a pattern, someone else in the organization may have tried it before—and learned the hard way what works. RFCs surface that lived experience. Without them, you often don’t find out until after you’ve repeated the same mistakes.

A Messy Example

I’ve seen this play out across two very different types of complexity at the same company.

The first was a Product Catalog unification effort following several acquisitions. We were left with three legacy implementations. When the team leading the consolidation effort circulated an RFC, it didn’t just describe a new schema, it acted as a lightning rod for tribal knowledge. Teams we didn’t even realize were catalog-dependent flagged edge cases that would have broken their specific domains. The RFC forced us to incorporate “scar tissue” from previous integration attempts early in the process. Without it, that knowledge would have stayed siloed until it caused a breaking change in production.

The second was a platform-wide shift to Keycloak for authentication. This wasn’t about data domains; it was about cross-cutting infrastructure contracts. The RFC surfaced critical dependencies across API gateways, OAuth flows for human users, and service-to-service auth patterns. These are the types of changes that usually result in a high-priority incident because a team halfway across the org realizes a core assumption changed without their knowledge. By moving that realization to a document, the team was able to standardize the contract and the migration path months before the first service cut over.

In both cases, the RFC didn’t just “document” the work, it debugged the organizational logic while changing direction was still manageable.

The Tradeoff: Meetings for Reading

RFCs don’t eliminate communication overhead—they shift it. Instead of sitting in meetings, engineers spend time reading and writing. This is a real tradeoff, not a free win. Your organization needs to be comfortable with async communication as a primary mode, not just a backup when calendars don’t align. Some engineers thrive in this environment; others find it harder to engage with a document than a conversation. Neither preference is wrong, but you’re making a cultural choice when you adopt an RFC-driven process. If your organization already leans async, RFCs will feel natural. If your culture is built around real-time collaboration, expect an adjustment period—and be intentional about which decisions still warrant synchronous discussion.

A regular architecture meeting where engineers present RFCs to engineering leads can bridge this gap. It gives people who prefer real-time discussion a venue to engage, while the written RFC ensures anyone who can’t attend still has full context. The discussion results then are incorporated into the document. The meeting complements the async process, it doesn’t replace it. Some engineers do their best thinking in writing; others need the room to talk it through. Having both channels means neither is shut out.

The Bureaucracy Trap

Here’s where most RFC processes go wrong: they become the thing that good engineers hate. You’ve overcorrected if RFCs are required for trivial decisions. If templates take longer to fill out than the actual implementation work. If approval bottlenecks mean engineers are blocked waiting for sign-off. If the process feels like compliance rather than collaboration. An RFC should help engineers make better decisions faster.

What’s RFC-Worthy vs. Overkill

The goal is to avoid the “Bureaucracy Trap” by providing a clear mental model. An RFC is warranted when a decision has blast radius or reversibility cost.

Here are some good rules of thumb. Write the RFC if the decision:

- Affects multiple teams: Changes a system boundary, API contract, or shared interface.

- Has high “one-way door” cost: It will be difficult, expensive, or politically painful to undo in six months, a year, etc.

- Introduces “Organizational Debt”: New languages, new databases, or deprecating a core service.

- Impacts compliance or privacy: If Legal or Security will have questions later, the answers should be in an RFC now. This also applies for things like ISO, NIS, and the like.

The RFC is likely overkill when:

- The change is easily reversible. If you can undo it in an afternoon, just do it.

- It’s an implementation detail. If you’re deciding how to write the function, not why the service or system exists.

- It follows an established pattern. Don’t re-litigate the company’s standard for Postgres schemas every time you add a table.

- The decision is entirely contained within a single team…

- …unless that team is a “guinea pig” for a technology or service the rest of the org will eventually adopt.

- …unless the decision creates a precedent that will eventually “leak” out of the team’s domain.

- …unless you know another team has experience or “scar tissue” in this specific area and you need solicit their feedback.

The “unless” cases are where engineering leader’s judgment lives. If an engineer is in the gray zone, bias them toward a “Lightweight RFC.” A one-pager that gets a “Looks Good To Me” (LGTM) in ten minutes is a small tax to pay for avoiding rework.

Making the Call

The underlying question is simple for engineers: does this decision need to be visible and reviewable beyond my immediate team? If the answer is yes, write the RFC. If the answer is no, make the call and move on. If you’re not sure, bias toward writing it, but keep it short and sweet.

RFCs aren’t about asking permission; they’re as much about building a culture where ‘I didn’t know’ is no longer a valid excuse for architectural drift, as they are a way to ensure democratization of information without creating meeting overload. As a leader, your job isn’t to read every RFC—it’s to ensure the process exists so that the right people can read them. If you don’t formalize how context travels, don’t be surprised when your teams start moving in different directions.