I’ve watched companies outsource their competitive advantage because “the vendor was cheaper.” I’ve seen engineering teams spend months building authentication systems from scratch because “we’re a technology company, we build things.” Both mistakes stem from the same root cause: failing to distinguish between core competencies (what makes you unique) and core capabilities (what you need to operate). The categorization sounds simple, but in practice it’s where most strategic tech decisions go wrong, and the consequences compound over time. Outsource a competency and you’ve ceded control of your roadmap. Treat a capability as strategic and you’ve turned your engineering team into a maintenance organization. Neglect your culture and people start questioning your decisions.

Definitions

Core competencies are what make your company unique: the capabilities, whether customer-facing or internal, that create or enable your competitive advantage. If you’re a logistics company, your routing algorithms might be a core competency. If you’re a fintech, it could be your fraud detection system. For an e-commerce platform, it might be the personalized recommendation engine that drives conversions.

Core capabilities are essential to running your business but don’t differentiate you: authentication, payment processing, analytics, CRMs, ERPs, etc. These are table stakes. You absolutely need them, but your customers don’t choose you because of how you implemented SSO.

The distinction matters because the strategic approach to each is completely different. And critically, functions can shift between categories as your business evolves.

Not everything starts as a core competency. A food delivery company might start with off-the-shelf routing but discover that custom dispatch algorithms, optimizing for speed, cost, and driver satisfaction simultaneously, become their competitive edge. A healthcare tech company using standard scheduling might find that patient flow optimization becomes a key differentiator.

The triggers for this shift are usually market-driven: competitors start winning because of a capability you thought was commodity, customers explicitly choose you based on how you handle something, or improvements to a “good enough” function create measurable competitive advantage. When you spot these signals, recognize that what was once a capability may now require the protection and investment of a core competency.

Litmus Tests

When you’re unsure whether something is a core competency or a core capability, a simple litmus test can help. These aren’t universals, but a good general guide.

- Does this directly contribute to our differentiation in the market? If customers choose you because of how you do this, it’s a core competency; if they only need it to work, it’s a capability.

- Would losing the ability to do this in-house materially weaken our strategy? If outsourcing it would undermine your strategic position, it’s a competency; if you could swap vendors without changing who you are, it’s a capability.

- Does improving this function materially strengthen our competitive advantage? If better performance here creates outsized strategic value, it’s a competency; if it merely brings you up to industry standards, it’s a capability.

- Is this area deeply tied to proprietary knowledge, IP, or organizational identity? If it relies on unique expertise or represents something you want to be great at, it’s a competency; if the skills are widely available or commoditized, it’s a capability.

- Would outsourcing this create long-term strategic dependency or lock-in we can’t easily unwind? If a vendor could gain leverage over your roadmap or ability to innovate, it’s a competency; if multiple interchangeable solutions exist and migration is feasible, it’s a capability.

Core Competencies: Protect and Document

For core competencies, outsourcing the entire function means outsourcing your company. The primary decision isn’t whether to keep these in-house, that’s a given. It’s about how to structure and maintain that knowledge internally.

You can outsource parts of a core competency. You might hire contractors to help build features or use offshore teams for specific components. But the architecture, the decision-making, and the institutional knowledge should stay internal. More importantly, that knowledge needs to be documented and distributed. If your competitive advantage lives in one person’s head, you don’t have a core competency, you have a single point of failure.

The real work here is organizational: ensuring knowledge transfer, maintaining technical documentation, and building systems that preserve your advantage or put you further ahead of the competition, even as people come and go. This is where your senior engineers should spend some of their time, where your architecture reviews should focus, and where you should be most resistant to “let’s just use a vendor for this.”

Misclassification of a core competency happens most often under pressure, when teams are trying to save money, move faster, or plug an immediate resource gap. It’s also one of the easiest ways to erode long-term advantage. A core competency can quietly get treated like a capability because “a vendor already does this” or “we just need to get something out.” Once that happens, you risk losing the internal expertise that differentiates you. This leads to competency drift, where small, incremental outsourcing decisions slowly hollow out the feature sets (and how they work together under one solution) or knowledge that once made you competitive. By the time you notice, the strategic heart of your business is effectively owned by someone else, and rebuilding that competency is far more expensive than protecting it in the first place.

Core Capabilities: The Build vs. Buy Decision

Core capabilities require more nuanced thinking. You need them, but you have options for how to acquire them. Miscategorized capabilities are often a hidden tax on your organization’s attention. The decision framework should consider several factors:

Control and customization: How much do you need to tailor this capability to your specific needs? Payment processing for a standard e-commerce site is different from payment processing for a multi-sided marketplace with complex fund flows. The more your requirements diverge from standard offerings, the more control you need.

Strategic optionality: What does the future look like? If you’re domestic now but plan to expand internationally, vendor lock-in could constrain your options or make your system(s) much more complex. If you’re small but planning to scale rapidly, make sure your solution can grow with you. The cheapest option today might be the most expensive option tomorrow.

Reversibility and vendor lock-in risk: Not all build-vs-buy decisions can be easily undone. Some choices create deep structural dependencies; on a vendor’s data model, on proprietary workflows, or on custom code that only a few engineers understand. When evaluating a capability, ask how hard it would be to switch vendors, rebuild internally, or redesign around a different architecture. If the answer is “painful, slow, or disruptive,” you’re dealing with a low-reversibility decision and should evaluate it with the same rigor you’d apply to a core competency. This isn’t just about migration cost, it’s about what happens when the vendor raises prices, changes their roadmap, or gets acquired. In some regions, data portability requirements can work in your favor here; factor that into your assessment.

Total cost of ownership: A vendor solution has subscription costs and often implementation costs. An open source deployment has infrastructure, maintenance, upgrade, and engineering/devops time costs. Building custom has development costs plus ongoing maintenance. Don’t just compare sticker prices, factor in the full lifecycle cost including your team’s time. Just because you aren’t paying vendor costs, doesn’t mean you aren’t paying the price of spreading your team thin.

Deployment and maintenance complexity: Some open source solutions require significant expertise to run well. Some vendors handle everything. Some custom builds become technical debt nightmares. Be honest about your team’s capacity and expertise and how that factors into TCO (Total Cost of Ownership).

AI-generated code deserves special caution here. The speed is real—you can prototype a capability in hours instead of weeks. But that speed creates a new form of technical debt: systems that work but weren’t designed to integrate, scale, or evolve. If you’re reaching for AI to solve a capability gap, be honest about whether you’re prototyping or building. The distinction matters when that “quick solution” is still running two years later.

“Build” doesn’t necessarily mean writing everything from scratch. Deploying and configuring open source software from GitHub is building. Using AI to generate a customized solution is building. The question is whether you’re taking on the responsibility of maintaining and evolving that capability.

Organizational Context

The technical framework is necessary but not sufficient. In practice, the framework only works if you have a clear decision-making process that weighs strategic value over departmental preferences, and most organizations don’t.

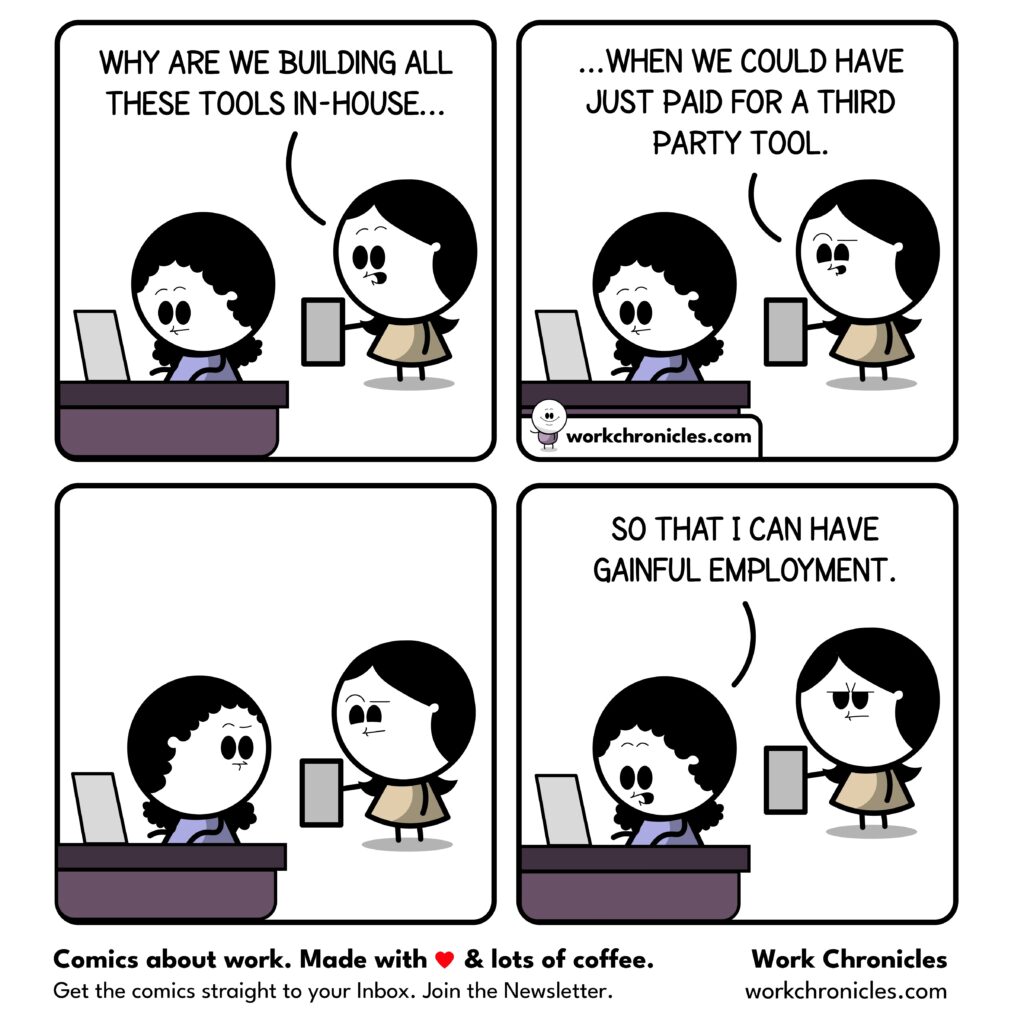

Engineering teams want to build because it’s fun and interesting, looks better on a resume, and building is what engineers do. Finance teams often don’t want to buy either since vendor costs hit the bottom line while in-house costs are already “paid for.” Product teams want whichever option leads to engineering shipping faster. When these incentives collide, the loudest voice or the person with budget authority usually wins, not necessarily the right strategic answer. As C-levels and senior leaders, it’s your responsibility to name this dynamic and create space for the actual strategic conversation.

Culture shapes these decisions more than leaders like to admit. Companies that pride themselves on craftsmanship or owning the full customer experience will naturally treat more things as core, building is part of their identity. Others that prioritize pragmatism or operational efficiency will lean toward buying unless something is clearly strategic. Neither stance is wrong, but misalignment between cultural instincts and strategic intent leads to inconsistent decisions. Know your organization’s defaults so you can recognize when you’re building out of ego or outsourcing out of habit.

Finally, regulatory and compliance requirements can override the entire framework. In heavily regulated industries, you may need to build capabilities in-house simply because no vendor can meet your compliance requirements, or because vendor integration compresses margins beyond viability. Factor this in early since compliance-driven builds are expensive, and discovering this mid-evaluation wastes time and hurts credibility.

What Happens When You’re Wrong

You will miscategorize things. A capability you thought was strategic turns out to be commodity. A function you outsourced as “non-core” becomes central to how you compete. The question isn’t whether you’ll get it wrong, it’s how quickly you recognize the mistake and what you do about it.

The warning signs are usually obvious in hindsight. When you’ve treated a competency as a capability, you’ll notice your roadmap is constrained by vendor limitations. Feature requests pile up that you “can’t do because the vendor doesn’t support it.” Competitive threats emerge from companies who built what you bought. Your engineers start saying “we should really bring this in-house” with increasing urgency.

When you’ve treated a capability as a competency, you’ll see your engineering team drowning in maintenance work that doesn’t move the business forward. You’re rebuilding features that exist in mature vendor products. Your “strategic” system is consistently deprioritized because there’s always something more important. The business questions why engineering built something they could have bought.

Course-correcting is expensive. That’s why we considered reversibility as a factor upfront. Moving from vendor to in-house requires hiring, knowledge building, and often a lengthy migration while you run both systems in parallel. Moving from in-house to vendor means admitting sunk costs, managing the migration complexity, and potentially losing engineers who built the thing you’re now abandoning.

The key is revisiting these decisions regularly; typically whenever your business model or competitive landscape shifts significantly. What was right at your Series A may be wrong at $30m in ARR. What differentiated you last year may be table stakes this year. Treat the framework as a living assessment, not a one-time categorization.

Making the Decision

For core competencies, the question is “how do we protect and scale this advantage?” For core capabilities, the question is “what’s the right balance of cost, control, and flexibility for our current stage and future trajectory?”

Early-stage companies might vendor almost everything to move fast. That’s fine, as long as you’re clear-eyed about which vendors are wrapping your core competencies (dangerous) versus enabling your core capabilities (pragmatic). As you grow, you might bring some capabilities in-house for better control or economics. Also fine, as long as you’re making the tradeoff consciously. What’s not fine is confusing the two categories. Treating a core competency like a capability and outsourcing it away. Or treating a capability like a competency and wasting engineering resources on something you could buy.

The logistics company that outsourced their routing is now waiting on their vendor’s roadmap. The team that built auth from scratch is still maintaining it three years later. Both made defensible decisions at the time. Both are paying for them now.

Get this right, and you build a technical foundation that enables competitive advantage. Get it wrong, and you’ll spend years unwinding decisions you didn’t realize you were making.